- Home

- Winnie M. Li

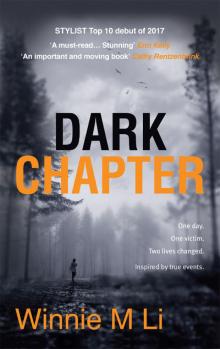

Dark Chapter Page 3

Dark Chapter Read online

Page 3

Currrrl back. From now on, only those beautiful rounded Rs, the way they’re supposed to sound.

*

He is three and this is his earliest memory: music. Laughter. Heat coming from an open fire. At night, on a field. Looking up at the stars. Shiver with the cold. Breath puffing into the air. Playing hide-and-seek in the mud, between caravans. Giggling with his babby sister, Claire. Michael knocking him over, then showing him how to punch. Granda tossing him into the air, his ring shining in the firelight. Snuggling up to Mam when the night gets too cold.

The smell of whiskey being passed around. Adults laughing. The fire dying down.

Later, inside, Da shouting and Mam shouting back. He hides under the table when this happens. Da hitting Mam, again and again. Da falling asleep. Mam still crying, huddled in a mound.

She looks up at him, face all dark and wet. He crawls round to her. “Come on, Johnny. Off to bed with you now.”

*

Sunday mornings, and she’s always sprawled on the kitchen floor, reading the newspaper. The floor tiles stick to her skin, especially in the summer since her mom never turns on the air conditioning to save money.

But she doesn’t mind. The Sunday paper arrives as a thick brick of newsprint, all different sections folded into layers. She’s twelve going on thirteen, and she can spend hours reading it, while Serena’s busy practicing piano. Propped up on her elbows, her stomach pressed against the floor and legs swinging upward, she leafs through the big pages.

Mom walks around her and washes the breakfast dishes. Dad always reads the Business section, which is boring. For Current Events in class every Monday, she has to pick out an article from the front section and talk about it. Once, she cut out an article about how a dead woman was dragged from the Passaic River. “A woman’s naked, beaten body was discovered.” The boys giggled, and the teacher yelled at her for choosing such a violent story. Guess she was supposed to be reporting on peace talks or a Supreme Court case or something boring like that.

But it’s the Travel section she reads cover to cover. Everything from vacation destinations to special cruise-ship deals in the Caribbean to train itineraries through the Norwegian mountains. There are so many questions in her head: how do you fly to Turkey? What’s the difference between all those Caribbean islands? How long does it take to walk the Appalachian Trail?

The newspaper covers North Jersey, and sometimes it talks about a museum exhibit or a play that’s on. Then she’ll look at the location of that museum or playhouse, unfold a map of New Jersey onto the floor, and try to find the town where it’s located.

The map sucks her in, she could study it all morning. The paper’s edges are frayed and fuzzy where the map is folded into rectangles, and she has to be careful not to tear the map apart. The towns are all squashed up next to each other, sometimes a river or a highway separating one from the next. She’ll try to figure out how to drive from Edgewood to that museum or playhouse, following the familiar highways, tracing down this interstate or that to get to her destination.

She knows that really, they will never end up going to see this play or that museum exhibit. Her parents are too busy running the dry-cleaning shop, and they don’t have the money for those kinds of trips. But if she did ask them, if they did say yes, she could tell them right away how to drive there. Knowing how to get there is close enough to actually going. There is some small satisfaction in that.

She will look at the map, noting where the parks are. The state parks spreading as giant green swathes on the map, and the regional parks, and the lakes and the rivers. Try to match what’s on the map with what she can remember from drives with Mom and Dad. But the maps always extend farther than she knows. And the more she looks the more she sees how many towns there are in New Jersey, how many lakes, and how the interstates run past the borders of New Jersey into Pennsylvania, Delaware, New York. And that’s just this one corner of the USA. She thinks of all the highways connecting all the states, all the different parks and lakes and townships, right across the continent. So many places, she’ll never get to know them in her lifetime.

At night, she often has trouble falling asleep because she’s thinking about these maps and the places beyond the borders. Imagine the possibilities, towns and hills and valleys waiting to be discovered. If you go all the way across the country, you’ll get to places John Steinbeck wrote about. If you go halfway across, you’ll hit Kansas, where the cyclone transported Dorothy to Oz. Even close by, in New York City, is where Holden Caulfield walked forty-one blocks to get home late at night.

So many places she can visit when she gets older. She lies there in her narrow bed, wedged between the piano and the corner of the room, and she imagines riding along those highways on the map. Roads leading everywhere and beyond. Sleep can come later; she’s too busy imagining. She shoots down an interstate and a string of towns passes her by. She reaches the top of a ridge, like in those TV shows about pioneers, and a whole valley spreads open below her.

*

Him and Mam are going to the Garda station in Kilkenny, where it slopes up from the cathedral. Women shoppers are rushing past. A few old men hang around on benches.

Mam marches right up to the police station. She wanted to hold his hand, but he lurks behind, better for looking at people.

She pushes open the blue doors of the Garda station, and waits, impatient for him to follow.

Inside the lights are bright and it’s nice and warm. But they don’t feel welcome here. There’s a counter and a few men behind it. Michael calls them pigs. They look at him and Mam grim-faced. Stiff and mean in their uniforms.

“Can I help you?” one of them asks. He looks around Da’s age, dark hair with white streaks.

Mam pauses. Then finally speaks. “I, ehm… I’m here looking for me son. You have me son here.” Her hands shake as she grips her red handkerchief.

The pig’s face changes, not in a good way. He sorta grins, looking at the other two pigs, then back at Mam.

“And what makes you think that?”

“You… you found him in the sporting goods shop on Ormonde Street. His name is Michael Sweeney. He’s fourteen years old, brown hair. About this high.”

She gestures with her hand, above her head.

“Mi-chael Swee-ney,” the police says, stretching the name out. He asks one of the others. “Tell me, sergeant, do we have any boy by that description in here?”

“Michael Sweeney,” the other one says. “Let me think…”

He can tell they’re making fun of Mam. It’s just a game they’re playing to wind her up. And it’s working, Mam’s fingers are twisting the handkerchief, twisting and twisting.

“Please, sir, just tell me if you have him.”

“And would you happen to be Mrs Sweeney?”

“Yes, yes I am.”

“And is this Michael Sweeney’s younger brother here?” The pig turns and stares directly at him. He don’t like the way he’s being looked at.

“Yes, yes. My Johnny. He’s only eight.”

He looks back at the pig, tries to look cold and mean.

“Only eight?” The police nods at the others. “Tell me, Mrs Sweeney… Are you residents of Kilkenny?”

“I… we…” Mam stops, nervous. “We are staying here in Kilkenny at the moment.”

“At the moment… and what do you mean by that?”

“We’ve been here a few weeks.”

“And does that mean you’ll be leaving Kilkenny soon?”

“Well, no, not sure. We don’t know yet.”

“Ah, so you move around, do you?”

“Well, yes, we do. That’s how… that’s how we like to live.”

“How – we – like – to – live,” the pig repeats Mam slowly. “And tell me one other thing, Mrs Sweeney… This way that you like to live… Does that also involve letting your son steal from honest, hard-working people? Settled people, as I once heard your kind say?”

He is talking stra

ight at Mam now.

She don’t know how to answer. He’ll die of embarrassment if Mam starts crying again, right here in the police station.

“Answer me, you knacker! Do you think it’s all right for your son to go around stealing from our businesses, because he’s bored, unschooled, because you don’t know how to discipline your twelve children and we have to suffer all the time from the likes of tinker scum like you?

Mam is trembling.

“Mrs Sweeney,” the pig booms at her. “Do you think that’s all right?”

Mam finally finds her voice, tries to control her breaths.

“No, no, of course not, no. No, it’s not all right! And I don’t want my son doing this, I just want him to be a good boy, and I don’t know why he does it. I am sorry, and I really truly apologise.”

Somehow, the way Mam is acting makes him sick. He wants to walk out of the station, forget she’s here. Other people don’t act like this in front of the pigs.

The pig snorts. “Apologise all you want. That’s not going to help. It’s us who have to deal with criminals like your son. He’s been a terror to businesses since you got here. Stolen from other shops, lifted handbags off the street. We’re glad we finally caught him.”

Mam looks shocked, but he’s known all along about Michael. Them nights when Michael came home breathless, a haul stuffed in a black bin liner. Purses with money in them, phones and fancy make-up and scarfs and all them things women carry around.

“It’s dead easy,” Michael told him. “Once you get the hang of it. Look for women with prams. They’ll never be able to chase after you. Or older women. But if your one has a man with her, that’s too risky”

If there were sweets or coins, Michael gave them to him. “Till you’re able to pinch your own,” he’d say with a wink.

Any money, Michael would stuff into his own pockets. He’d open up all the phones, take out the tiny cards and toss them with any credit cards. But everything else had a use: the phones, purses, key chains, scarfs, even the make-up. Michael would polish them up, put them back in a black bin-liner and knot it tight.

“What you doing with those?” he’d asked.

And Michael just winked at him. “I’ll tell you when you’re older.”

He knows all this but of course hasn’t told Da or Mam, and now Mam looks shocked and embarrassed here in the police station.

“Me Michael?” she asks, still about to cry. “He was always lively, but a criminal?”

“You need to open your eyes, Mrs Sweeney. Your son is more than just a lively boy He’s a proper thief. We caught him trying to stuff two pairs of expensive trainers under his coat. Where’s your son learned to do that?”

“Not from me! I take them to church. I teach them to be good.”

“Yeah, well, it doesn’t appear to be working. So maybe the best thing we can do for him is put him in a detention centre for a little spell.”

Mam seems to be choking. He wants to keep on staring at her, but he ends up looking away. “Jail for me Michael? No, please, sir…” Mam is pleading now.

But the pig just looks down at her. “A detention centre is the best thing for your son, Mrs Sweeney.”

“No, he’ll die there. It’ll be terrible.”

“Oh, come off it. He’s a little shite and needs to be taught a lesson.”

“Oh, please just give us one more chance. Don’t send him away this time. I’ll teach him. I’ll teach him to be better.”

“You’ll teach him? I think you had your chance, Mrs Sweeney. Maybe if you stopped moving around so much, got proper jobs, and sent your kids to school…”

He hates the policeman something deadly. Didn’t like him to begin with, but right there, he fills up with hatred. Clenches his fists, the way Michael taught him.

“How… how long will you send him away for?”

“It’s all up to the courts, this matter. We have witnesses, of course, but for something like this, a few months, maybe? It’s better to get them disciplined early. Prevent anything worse happening later.”

“Oh, please, believe me. He won’t do anything like this ever again. I promise.”

The pig only laughs. So do the other two behind the counter.

“Mrs Sweeney, you have no idea.”

Mam is quiet then.

“The facility is north of Dublin. You’ll be able to visit him once a week. So that might affect you moving around so much. But think of it this way, at least he’ll be getting three square meals a day. Probably better than, ehm, what’s at home.”

He looks hard at Mam, and she goes cold then.

The pigs are grinning, nodding, shuffling papers on their desks.

“Come on now, Mrs Sweeney. I’ll let you see your son for a bit. No use in crying over this one, he’s gone down a bad path. We just have to see if we can get him off it.”

The policeman moves to a door on their left. Unlocks it with a jangle of keys and looks impatiently at them. Mam makes for him to come along, and he does. But before going through, he shoots another look at the pig, a black, cold, hard glare. He wishes that pig would drop dead, right then and there.

*

She’s working in her parents’ shop, tagging the dry-cleaned clothes, stapling the papers through the plastic sheeting, when she hears the news.

It’s April, she’s thirteen, and she has to do two hours in the shop, before one hour of piano practice, and then her homework. Dad is in the back doing the accounts. Mom’s been antsy all week. She knows the Ivy Leagues are mailing out their decision letters, so every day, she’s out the door the moment the mailman drives away.

Already, Serena’s been accepted into Yale, Princeton, Georgetown, Cornell, UPenn, and Rutgers (which was the safety school). She applied to ten schools in total, and the only big one left to hear from is Harvard.

Mom has been mentioning Harvard for as long as she can remember. Last summer, they went on a college campus tour for a week, driving around New England and visiting the major Ivies. It was the first time they’d gone on vacation in years. She liked walking through the college campuses, the wide green lawns, and the big ancient buildings with the Gothic arches and the vines crawling up the walls. Everything seemed so quiet and peaceful. So old. The tour guides told stories about the buildings, but part of her wanted to wander off on her own, among those stone columns and steps, and get away from the crowd of people.

Anyway, she can see why Serena wants to go to Harvard. They had some of the oldest buildings, right alongside a river, and after the tour, they bought sandwiches and sat on the grass by the water. The college buildings rose up along the river banks, towers with domes and clocks, and it seemed like a whole different world – an ancient, magical world – so different from here in New Jersey.

She looks up as the shop door pushes in, and Mom and Serena are practically running in, big smiles on their faces.

“She did it! She did it!” Mom screams.

Dad rushes up from the back, and Serena’s jumping for joy. “I got into Harvard!”

“I knew you could do it!” Mom is shouting.

Dad gives Serena a big hug. “See, I don’t know what you two were so worried about.”

She feels the joy bubbling up inside of her, too, and she gives Serena a hug. Has it actually happened? Harvard? “That’s so cool,” she says.

Serena shrugs. “Well, I still have to decide where to go.”

“Of course you’re going to Harvard,” Mom says, as if there’s no question. “Now that you got in.”

Just then, the shop door opens again and one of their regular customers, Mrs Weissman, walks in. Mrs Weissman is an older woman, sixties or so, with short hair dyed orange and wrinkled hands. Mom shares the good news with her. “Can you believe it? My eldest daughter, she’s going to Harvard! She just found out.”

Mrs Weissman claps in delight. “I always knew you were a smart cookie. Well, you must be so proud of her.”

“I am, I am. I’m very proud of her,”

Mom says. Despite all the straight As, the piano competition trophies, the high test scores, Mom rarely says anything like this. These things are just expected. Mom turns from Serena and Mrs Weissman, and looks to her, smiling. “Now, I just have to make sure this one gets in, too.”

*

He’s nine and is going to school in Dublin for a few weeks now. Traveller kids mixed in with settled kids, though not really. There’s a big stripe down the middle of the schoolyard. Travellers play on one side, buffers on the other.

Of course, after enough scraps, he ended up in the room for really bad boys on the first day, the ones the teachers don’t bother teaching no more. There’s a few things he can learn from these boys, even the buffers.

One of them, Joe, must be rich. He can tell by his clothes and shiny shoes. Joe’s always too smart with the teachers. Never gives them what they want. Joe talks to the teachers like they’re dirt, and they hate that.

He secretly loves it. Wishes he could speak to them the same way.

But he remembers what Mam says: “Don’t be giving us Travellers a bad name when you’re at school. Be respectful. Listen to the teachers.”

But why listen to them? They’re boring and they hate me anyways.

Joe asks him loads of questions: where is he from, how long they been in Dublin, what do Travellers eat. Joe says they’re lucky they don’t have to go church or talk to neighbours. It’s the first time he hears a buffer call him lucky.

“You lads have it good. You can always feck off whenever you want.”

But Joe is the best when it comes to girls. Always has something new to say.

“You have any sisters?” Joe asks him once, when they are hanging about on the street after school.

“Yea, I gots two. Claire and Bridget.” He kind of spits their names out, the way he spit out that stuff the school nurse made him take.

“How old are they?”

“Claire’s seven and a pain in me arse. Bridget’s just a baby. Just started walking.”

Dark Chapter

Dark Chapter