- Home

- Winnie M. Li

Dark Chapter Page 2

Dark Chapter Read online

Page 2

Why she is buying them now, she has no idea. They aren’t any easier to cook than a Tesco ready-meal. But she had come to Camberwell for her first assessment at the Maudsley Hospital, and the Wang’s Supermarket had been right here on the high street, smelling just like the Chinese grocery store of her youth.

As she wanders the aisles, the store speakers play a Chinese-language song, one of those half-wailing renditions seemingly voiced by a suicidal middle-aged woman, singing about love and loss. It’s something her mother might listen to, but it holds no meaning for her, other than an uncomfortable familiarity, just like anything Chinese that she encounters in her adult life.

She selects four ramen packets, a can of baby corn and a tall bottle of soy sauce. She pays for them with a five-pound note and steps out of that musty space onto the street, the Chinese soundtrack still ringing in her ears.

A group of youths push past, coming home from school in their uniforms. They are black, all five of them in their early teens, shouting loudly, and she pays them no heed. Drifts past them, oblivious.

At the bus stop, there is another group of teens. There are three of them, white, and they are looking at two girls on the sidewalk. Snickering, and making some comment she can’t hear.

She brushes shoulders with one of them as she steps onto the bus. He turns and looks at her for a moment. She can’t quite gauge what is in his look – adolescent lust or rage or maybe just annoyance. But his ice-blue eyes lance through her, almost recognizable, and her stomach turns. Sweat stands out on her forehead. Stumbling her way up the stairs, she sits down, tries to quell the rising nausea in her gut. She watches as the teenage boys continue down the street, knowing he is not the one, he is just some other teenage kid with a slight resemblance.

But the shame of it all. That even a passing encounter with a random schoolkid can cause this much disruption.

The nausea wells up, yet she controls it, keeps it at a manageable level. She will not be sick. Just haunted. She draws her knees to her chest and hugs them, curls up into a ball and looks out the window, as the bus draws away from the curb.

*

For a moment, he can’t remember how he got home. Still in clothes from the night before, head pounding. Must’ve fallen asleep on the couch. Late morning, and the sun streams in through the window, too bright. Birds chirp somewhere.

Da is out, and his brother, too.

Then he remembers: just a few hours earlier, swaying in the dark street with Gerry and Donal, drinking a mouthful of cheap whiskey and then another. There’d been pills that night. And dope. He remembers wandering into a pub with the lads, getting chased out by the owner. Then hunkering down at Gerry’s and watching porn.

He’d seen this one before. Where she bends over to blow your man and you can see everything, everything. That gaping pink hole between her legs, so alien and bizarre. Like some extra-terrestrial mouth out of a sci-fi film, only this one comes with tits, giant ones, enough to make you hard just thinking of them.

He thinks about them tits and already, with the sun streaming and the birds chirping, feels himself stir.

He reckons it’s too early. Even though he’s got the whole place to himself.

He looks round. Da and Michael are out for sure. But save it for later. Besides, he’s got a smashing headache and happens to be starving. Fucking ravenous.

Still reeling, hungover, he staggers to the caravan’s cramped kitchen. Pulls open the refrigerator, the cabinets, finds a quarter packet of biscuits.

Biscuits. Fucking biscuits for breakfast.

A half-drunk mug of water sits on the counter and he drinks that, scarfs down the biscuits, leans against the counter. Another search through the cabinets, but there’s nothing, only a mouldy loaf of bread, expired six days ago.

His stomach gurgles, hungrier than before the biscuits.

Christ, how long did Da say he’d be gone for? Four days, was it?

He sits back down on the couch, cradles his head in his hands. Maybe them pills haven’t worn off. Maybe he’s still rolling and can go another few hours without eating. Wouldn’t that be grand?

Oh Jaysus, it’d been a good night. The look on the pub owner’s face, the three of them legging it out the back door, packets of crisps in their arms. The sting of the whiskey down his throat, the spin of the night air after he took them yokes.

He cracks a grin at the thought of it, wishes one of the lads was with him now. But he can’t remember what came of them, or how he got back from Gerry’s.

Silence. Sunlight. Then he hears a pebble crack against the outside of the caravan.

It’s that little gimp from next door.

Sure enough, a toddler’s voice cuts through the morning, the mam shouting something miserable at him from their caravan. Another pebble hits the wall.

He clenches his jaw, realises it’s still aching from the night before.

Another pebble. Plink.

Annoyed, he bursts out of the caravan, the sunlight flashing into his eyes and he rounds on the toddler.

“Will you quit it?”

The toddler giggles and runs a few steps closer. Brown curls and stupid wide-set pale eyes that just laugh at him. Like he’s playing a game or something.

He scowls at the kid again, raising a hand like to slap him, and this time the kid squeals and runs inside.

He snorts and squints against the too-bright sun. Warmer today than it has been. Ten caravans crouch in the April morning, brilliant white against the green and brown of the field, and the sky races along the horizon, crisp and clear with the springtime.

For a moment, his hangover fades and he smells the mown grass and turned-up earth. Nice smells, but cut by the diesel of some engine in the next field over. Sunlight on his eyelids and he can stay there for another minute or two, his eyes closed, just him and the field. Summer is coming, and with it, long bright days when you can go out wearing only a T-shirt and relaxed tourists make easy targets. Warm evenings, girls in thin dresses, girls who want to let you touch them.

A child’s voice breaks his thoughts.

“Your da’s gone down to Armagh.”

He opens his eyes. “Yea, I know.”

The toddler watches him from a few metres away, leaning against the corner of the caravan. Christ, you can’t take a piss here without everyone knowing.

Speaking of, it’s about time for a slash. He turns and heads away, to the edge of the field.

“Where you going?”

He don’t answer. Just keeps walking away, feeling the kid’s eyes on his back. Twenty metres out, he stands on the ridge of the plateau and undoes his flies for a piss.

The wind pushes clouds along the horizon, and he sees Belfast stretched before him, a cluster of grey and brown buildings rising up in the ugly knot of the city centre, before reaching the sea.

Between him and the city, the glen winds down below, under housing estates and patchy fields. The sound of the river, loud with spring rains, drifts up to where he stands, shaking his last drops of piss onto the ground.

He breathes in the morning air. Best fucking view in the world for a slash.

*

“The West Highland Way. That’s the last one.”

She pushes the pin into the map, stabbing the mountains somewhere north of Glasgow, and sits down, satisfied.

“Okay, so only five long-distance trails,” Melissa says with a note of sarcasm.

“Five trails,” she nods. “I can do that. Sometime in my life.”

“So… you’re still going to be hiking these when you’re fifty?”

She laughs. God, fifty. “Hopefully by twenty-five I’ll have done all of these. Maybe thirty?”

She is eighteen and sits on her bed in the dorm room. Melissa flops down next to her, unkempt hair sprawling on the dark-green bedspread. For a moment, they rest in silence on the bed, staring up at the map of Europe dotted with its colorful push-pins.

“Viv, that’s nuts. You’re gonna do these all on yo

ur own?”

She shrugs. “Haven’t thought about it, but why not?”

After all, isn’t that the whole point? Thoreau living in solitude, off in his cabin by Walden Pond. Walt Whitman waxing lyrical about leaves of grass, writing under a tree while his beard grew longer and shaggier with the passing seasons. Edward Abbey drifting down a vast canyon in the American Southwest, the rock walls rising on either side of him, just him and the canyon.

“You’re completely nuts,” Melissa says, shaking her head. “Meanwhile, I’d just be happy if I could get Danny Brookes to have coffee with me.”

“Really? You’re still into him?”

“Well, until someone better comes along to crush on.”

She smiles to herself. At the moment, there is no one – not one boy on campus – who interests her. Maybe on the fringes of some crowd she has glimpsed a boy who looked thoughtful, different from the others. But boys in general, with their unfunny jokes, their swaggering need to be seen as confident in class… boys don’t hold much interest for her at the moment.

Melissa is still gabbling on. “I caught Charlie Kim staring at me a few times in Econ.”

“Would you be into him?”

“He’s kind of interesting. I’ve never kissed an Asian guy before.”

“Neither have I!”

They both break into giggles.

“But wouldn’t your parents want you to?” Melissa asks.

“What, kiss an Asian guy? At the moment, I don’t think my parents want me kissing any guy, to be honest.”

“You’re lucky.” Melissa reaches out and strokes her friend’s hair. “My mom keeps making these annoying comments. Have you found a nice boy yet? Any special someone in your life? I mean, we’ve only been in college four months!”

“I’m kinda glad my mom doesn’t ask me things like that.”

Another pause. It’s Friday night and from outside in the hallway, they can hear other students getting ready to go out in search of the loudest, most alcohol-fueled party. The boys at the end of the hall are bellowing; the girl next door shouts at them to shut up. Someone on the floor has turned up their stereo and the sounds of Oasis drift through several walls.

“You have the most amazing hair,” Melissa coos. She runs her fingers through Vivian’s thick black mane.

“It’s just my hair. It grows out of my head.”

“Yeah, but see what grows out of my head?” Melissa gestures to her own limp brown hair. “If I had hair like this…” She trails off, but continues to stroke the long black strands.

“What?” she asks, curious. “What would you do if you had my hair?”

“I’d… I’d… I dunno, I’d come up with the most amazing kinds of hairstyles for it. I’d wear it different every day!”

“Too much trouble,” she scoffs.

But Melissa jumps up, excited. “No, let’s do it! Do you have any bobby pins and hairspray?” She looks around the room, but hardly any hair products or accessories sit on the dresser.

“Doesn’t matter. I’ll figure something out. Honestly, this’ll be amazing.” Melissa gets up on her knees and begins brushing her friend’s hair. “You can wear it to the Sigma Chi party later tonight.”

And for a moment, she likes the thought of that. No longer the unsure teenager who only started wearing contacts two years ago. And maybe she can meet a nice boy who isn’t a braying jock. Someone who might make her heart skip a beat.

She winces a bit as Melissa pulls tightly at her scalp, too eager with her brushing. But she relaxes as the fingers work through her hair, sometimes plaiting, sometimes bunching the strands into elastics. She sits patiently and looks at the map on the opposite wall. The West Highland Way. The Camino de Santiago. The GR15. Trails that snake their way over hills and through valleys, somewhere on the other side of the world.

*

“Where’d you find this one?” Gerry’s asking, as he cracks open another can of Carlsberg.

“In the park.”

“What was she doing in the park?”

“I dunno, just going for a walk.”

“Anyone see you?”

“No.” There wasn’t a soul around. He’d made sure of that.

“So why you afraid? Think she might blab?”

He shrugs. As much as saying yes.

“She was also a bit older,” he finally ventures.

“How much older?”

And he can’t remember. It was all such a blur. He knew she was older and he liked that about her. Knows he asked her how old she was, and she answered straight away. Didn’t giggle the way some girls do. Only he can’t remember what she said.

“I dunno. Twenty-something.”

“Like twenty-one or twenty-eight?”

“Jaysus, Gerry, I don’t remember! I was still rolling. She was older than she looked.”

“And she looked like she was in control?”

“Well, yeah, sorta. In a strange way.”

Even though he had to punch her a few times, squeeze her throat to get her to listen.

*

She is eight when she first sees the book at Barnes and Noble. In the Edgewood Hills Mall, New Jersey. Legends and Folktales of Ireland. On the cover, there’s a circle of standing stones, a green hillside, a full moon. A path through the mist. A lone traveler walks on that path, past the standing stones, under the moonlight.

“Mommy,” she says. “Please, please can I get this book? It’s only $2.”

And of course, if it’s a book and it’s cheap, Mommy can’t say no as easy. Books are good for you. They’ll make you smart.

She smiles as she turns the book’s pages, looking at the pictures before reading the stories. Imagine being that person on the cover, walking on that path. Somewhere in Ireland. On her own. The moonlight silver on the standing stones. Imagine that.

*

“Your brother, Michael… he’ll be the death of me.” Mam is crying, as usual, and he wants to slap her to shut up. The way Da does. “Just in and out of prison, all the time. And at his young age already. I get worried sick thinking about him.”

He says nothing to Mam. She’s always griping about Michael. Embarrassing, how much she whinges.

He looks out the window, to the fields outside the caravan. They picked a good spot this time, here in Cork. Not so many houses near. Not so many buffers staring at them. Lots of open space for him and the other Traveller kids to run around.

“I’m going out,” he says. “Just for a bit. ’Fore it gets dark.”

“Johnny, you be a good boy,” Mam says and reaches to touch his face.

He jerks away from her. He’s not a babby anymore. Doesn’t need his mam touching him like that. What would the lads say?

*

In second grade, when she is six, a speech therapist comes to their class and talks to all the kids who speak funny. That includes her.

One by one, they go into another room and sit with the speech lady. The speech lady has short hair and her name is Jason. It’s funny that a woman has a man’s name and wants to look like a man.

“And what’s your name?”

“Vivian.”

“What a lovely name.”

The speech lady had her read out some sentences. Then she showed her a bunch of pictures and asked her to say what they were. Rabbit, Red, Lemon, Wheel, Giraffe, Snake.

Could she say the words real slow?

She says them again. Raaaaaa-bit. Rrrrr-ed. Leh-mon.

The speech lady nods.

“Very good,” she says. “You’re a very good reader.”

The next time she sees the speech lady, Mommy is there with her. They ask Mommy to say some words, too. The same words. Rabbit, Red, Lemon.

“Ah,” the speech lady says. “See, you get it from your mommy.”

Mommy laughs. “Really?” she asks.

The speech lady says she needs to work on the letter R and the letter L. And maybe a little bit of S.

Right now, she is not

saying her Rs the right way.

“It’s because your mommy is from another country, so she says English words differently.”

She never noticed she said things different from the others. Or her mommy.

“So every Tuesday, we’ll meet, and we can play some games to work on your Rs and your Ls, and you can start to say those nice rounded Rs. How does that sound?”

She nods. She likes the sound of that, but she notices all the other kids who have to see the speech lady are either the slow kids (the ones in the lowest reading group), or Priya, who is Indian, or Mo, who gets made fun of because his older sister wears a scarf around her head.

It’s a little embarrassing to be with the slow kids. But at least the speech lady is nice.

Every week, there is homework she has to do for speech. Funny things, like balancing a Life Saver on the tip of her tongue and curling it backwards five times. That’s so her Rs don’t sound so flat.

Or pressing her tongue against the back of her teeth and making the L sound. L–L–L.

Five months of R–R–R–R and L–L–L–L every Tuesday afternoon.

Her tongue gets tired, but she keeps trying. Currrrl it backward. Touch the roof of her mouth with the tip of her tongue.

And then, one day in spring, the speech lady tells her she doesn’t have to see her anymore.

“Your Rs sound beautiful! You’ve done it!” She gives her a certificate with a ribbon on it, blue for first place, and a big R with a Rabbit that she can color in Red.

“Now say it for me again: Rachel the Rabbit is Red.”

“Rachel the Rabbit is Red.”

The speech lady claps. “You should be very proud of yourself.” She gives her a hug.

She never sees the speech lady again. After that, no more Tuesday afternoon speech class with the slow kids and Priya and Mo. She’s back with the rest of her class, and her Rs sound different now. Like someone else’s Rs. Her tongue curls back automatically. It can no longer remember what it was like once to lie flat at the bottom of her mouth.

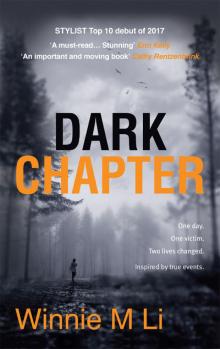

Dark Chapter

Dark Chapter