- Home

- Winnie M. Li

Dark Chapter Page 7

Dark Chapter Read online

Page 7

After Cork, the multiracial world of London is always a relief. There’s no one staring at her, commenting on her excellent command of English, men remarking on her ‘exotic looks’ and then asking for her number, as if that’s supposed to charm her somehow. She chafes at the thought of being judged merely by her appearance.

She has tried dating a few Irish men, but with little luck. Nothing’s lasted longer than a few weeks. This is unexpected compared to the steadiness of Hendrick, whom she dated in the last two years of college. Loyal, attentive Hendrick who gave her this very Lonely Planet guidebook. She broke up with Hendrick a year ago when she arrived in Ireland, knowing the country would somehow make less of an impression on her if her thoughts were constantly tied to a man who lived elsewhere. And at first, being single, she was pleasantly surprised by all the looks she drew in Ireland, the men who chatted her up in bars. But each of these guys, in their own way, turned out to be a disappointment, an unexpected source of pain. The men who stopped calling her after she didn’t sleep with them on the second date. She wonders if they were expecting something more sexual, something promised by her ‘Oriental’ looks.

Dating is a minefield. Too much potential for hurt, too much unpredictability.

And so she’s glad to be free of all that for a day or two, in this valley where she hasn’t encountered a single other human since she left the hostel this morning. To have all of humanity behind her, and just a trail ahead of her, waiting to be explored.

Now, the trail comes down the slope of the hillside and empties into the green bowl of this valley. She looks at her map again. The Coomarkane Valley ends with those two fantastic lakes: Derreenadavodia and Eekenohoolikeaghaun. They are as wild and remote and breathtaking as their names.

The valley gathers together at its head here, cradling the two lakes, while rocky cliffs clad in grass and heather rise up, forming the sides of the green bowl. Grass edges along the lakes, which sparkle blue and silver in the sun. When the wind blows, she can see it passing over the grass, then ruffling the surface of the lakes, an unspoken presence that quickly vanishes. She watches, mesmerized for a few minutes, while the shadows of clouds and the gleam of sunlight pass in turn over the grass, the water, the cliffs.

There is not another soul, not even a stray handful of grazing sheep.

She finds herself grinning, not quite believing her luck. To find a place this beautiful and abandoned, and to have it all to herself. She breaks out in a laugh, delighted.

She wants to rush forward into those green fields, but the trail has disintegrated and the grass is too wild to run through. Carefully, her eyes pick out a faint animal track, and she follows this toward the lakes. She wonders who was the last person to ever come to this valley.

The track leads down to the stream, which pours out of the lower lake. A flood of water runs rag-tag between scattered stones, so she has to pick her way across, leaping from one stone to another above the rushing water.

She does this too quickly and jumps onto a loose stone that skids through the water, before grinding to a halt against other rocks. A fall would have twisted her ankle, but she manages to stay on top, tensing her body.

Not a good idea to get injured out here.

Another hop and a jump and she’s made it to the other side of the stream.

She looks back at it. Nothing to be scared of really, a shallow slide of water, but it’s funny how scared you can get by the smallest of details once you’re out on your own.

She passes a sheep’s carcass embedded in the grass, as she starts to edge around the first of the lakes. Taking more care this time. It’s fairly easy at first, but a number of smaller streams flow down the walls of the valley and feed the lake. As the walls become cliffs, the streams become more vertical, until she finds herself practically having to jump across waterfalls that splatter into the lake.

She can’t see how deep the lake is, but she can hardly swim. Never had much of a chance to learn in childhood. Which makes jumping across slippery rocks hardly the safest thing to be doing alone.

After enough clambering past waterfalls, she reaches the far end of the lower lake, and she realizes this is where she should stop. The terrain is simply too rugged from here, and she doubts how much can be gained from struggling on any further. Even so, she looks longingly at the stretch of lush terrain between this and the upper lake, the wind blowing the grass from green to silver and back, the verdant slope of the valley rising up from the far side of the upper lake.

There’s always a farther place to go. Somewhere else to explore.

But no, she’ll stay here, have a snack, enjoy the view, congratulate herself on how far she got, and then head back. She checks her watch. 4:15. She’s aiming to catch the 6pm bus from Glengarriff to Cork, and even that’ll be a stretch.

It’s 5:30 and she’s hot-footing it back past the ruined buildings, down the road through the village.

As she walks, she realizes this will probably be the final time she’ll be in this valley. What are the chances that she’ll come here again, to this remote corner in the far southwest of Ireland?

No, in a few months she’ll be moving on. She’s decided that already. Rent may be cheap in Cork at 60 euros week, but it lacks the vibrancy and drive of London. From volunteering at the Cork Film Festival, she made a few contacts in London’s film industry. One director had handed her a card and said to call, if she was ever in town.

A few months later, she was having lunch with the lady in Soho House.

“After I finish my degree,” she ventured, “I’d be interested in moving to London and trying to work in film or television.”

The director said she would ask a few producers she knew. Maybe one of them needed an assistant.

Something about that sounds exciting, a possible trail that could lead somewhere new.

But for all her visions of living in that heady metropolis, she’ll need to get to Cork first. And right now, she checks her watch and realizes she has 20 minutes to catch the last bus. Only the bus stop is over 2km away. It’s virtually impossible to get there in time, unless she can manage to catch a lift.

In this remote valley, that seems highly unlikely.

She continues along the road at a fast pace, knowing that without a passing car, she is doomed to spend another night in this small forgotten town, on her own.

Her adrenaline picks up, while she curses herself for not leaving the valley earlier. But no, it was worth it just to see those two lakes.

Just then, she hears a car driving up the road, out of the village and back toward civilization.

Please be someone normal. Please be someone normal.

As it approaches, she can make out a gold-colored sedan.

She’ll always remember her scare in Germany when she backpacked for the travel guidebook. Hitchhiking isn’t a thing she wants to do, but sometimes time and geography and transportation schedules conspire to make you a bit more desperate.

The sedan approaches, coursing its way past the sprinkling of cottages.

Now or never, she thinks, and sticks out her arm to flag it down.

The car slows and stops.

A window is rolled down, and she is relieved to see a young mother with one girl next to her in the passenger seat, and two younger girls in the back.

“Do you need help?” the mother asks.

“Yes, I’m trying to catch the 6pm bus in Glengarriff. Is there any chance you can drop me off on your way out?”

The mother hesitates, glances at her daughters in the back. “Sure, no problem.” Her voice takes on a sharper tone. “Annie, Deirdre, make room for this young lady.”

“Oh wow, thank you so much. You’re a real lifesaver.”

She says this as the two younger girls shift over on the car seat, and she buckles herself in, her backpack nestled on her lap.

She’s aware of how broad and foreign her American accent must sound. She also realizes she’s covered in mud from her hike and apolog

izes for this. The mother says not to worry. “Hello.” She smiles at the two girls next to her.

But they just stare at her with wide eyes, half-disbelieving.

I must look like some swamp monster to them, stumbling out from the middle of nowhere.

She wonders if they’ve ever seen an Asian woman before, living as they do in this remote rural valley in Ireland.

The young mother is kind enough. “Where are you from?” she asks.

“America,” she answers. “New Jersey, near New York.”

She asks the mother if they’ve visited the States, but they haven’t. England is the farthest they’ve been.

“Are you traveling through?” the mother asks her.

“Mmm, sorta,” she answers. She explains she’s studying in Cork for the year, but had read about this walk and wanted to hike to see the two lakes in this valley. “Have you been there?” she asks.

“Not really,” the mother answers. “No one really goes there.”

And she wonders – to have a magnificent sight like that, right where you live, and to never see it. How strange it must seem to them, that people from as far as America would come here, to this forgotten valley to practically hike in their backyard.

The girls are still staring at her wide-eyed, but the car’s reached the main road now, and approaches the centre of Glengarriff. It’s really just a collection of pubs, a post office, church, school, hotels in the off-season, and one shop. And the bus stop.

“I’ll let you off here now,” the mother says, as they reach the Bus Éireann sign.

“Thank you so much, I really appreciate it.”

“Not a problem.” The mother nods at her, a close-lipped smile. “All the best, and safe travels.”

“You too.” She turns to grin at the girls in the back. “Bye now.”

They nod, still staring, and the youngest girl offers a shy, wordless wave. She waves back and the car drives off.

All quiet on the streets of Glengarriff. She walks towards the bus stop, where there’s no one else waiting. She checks the bus schedule, and then her watch.

5:58pm. Plenty of time to spare.

*

It is Halloween, she is twenty-five, and at 3:05 in the morning, she’s drunk at a costume party in the center of London. Fancy dress, as they say here in England.

Her own dress isn’t all that fancy.

She just put on a cheongsam which she had bought on her last trip to Taiwan, banded her hair up in a bun, pierced it with a few chopsticks, wore a redder shade of lipstick, and there you go – I’m your stereotypical Chinese woman.

Easy enough. Resort to the stereotype when it works for you.

This particular Halloween party is always a good one – the annual party thrown by this ex-pat American couple, the party everyone always wants to go to. The barricade of alcohol stacked up on the kitchen counter, the canapés, the live DJ, a pulsating mix of energetic, attractive 20-somethings from all over.

She had started talking to this rather cute English guy, Alex, who works for Morgan Stanley but is currently dressed as a vampire. They were talking by the cheeseboard, hungrily picking at the last of the canapés in a late-night case of the munchies. She’d had a lot to drink, smoked the odd joint that was passed her way. By now, the chopsticks have come out of her hair, stashed back into her purse, and her black hair falls loose, past her shoulders.

Most people are piling into cabs and heading up to an after-party, somewhere in West Hampstead. But it’s too far north for her, and she knows it’ll be more of the same, only with more drugs as the night stretches onwards. No, she’s ready to head home.

She stumbles into the spare room with all the coats, fumbles around in that giant slippery pile looking for her secondhand trench coat.

On her way towards the exit, a hand reaches out for her arm. It’s Alex.

“Hey, we’re heading back to ours in a cab. You live south, right? Wanna come with?”

He’s with his friend, flatmate, whatever. Tim. Who’s dressed as a pirate, although his eyepatch is gone. Pirate-Tim has been wearing eyeliner, which is now smudged.

“Which way you headed?” she asks. A cab ride sounds nice. No waiting in the cold for a night bus, no sharing a seat with an unknown drunkard.

“Clapham. We can drop you off on the way, or you’re welcome to come back to ours and have a drink.”

She understands the suggestion. She’ll consider it. This guy is cute, though he works in finance, like everyone else in London. Most people, for whatever reason, finds it ‘so cool’ that she works in television. They probably wouldn’t find her salary so cool.

“We have some good charlie back at ours,” he adds, as an extra incentive.

She’s not sure she finds this an incentive.

They find their way into a black cab, and as if by unspoken arrangement, Tim gets into the front seat, and she and Alex end up in the back. As they drive past Trafalgar Square, Alex’s hand finds its way to the small of her back, his fingers gently curving around her waist.

This doesn’t surprise her in the least. She’s still considering it. She is drunk. He is cute. And clearly interested.

He sidles in closer to her.

“Oh, can you make sure to go over Vauxhall Bridge?” she shouts up to the driver. “I’ll probably get off there.”

“Sure you don’t want to come back with us?” Alex asks, his face close to hers now. His other hand reaches to brush a lock of her hair from the side of her face.

She lets him do it.

“Come on, it’ll be fun. We’ll have a few drinks, snort some lines.”

The coke doesn’t interest her in the least, but before she can say anything, he leans in for the kiss.

She kisses him back – this is where it was always headed, after all. She closes her eyes, lets his tongue find hers. He’s not a bad kisser, but she is very aware that his mouth tastes like those cubes of cheese stacked up on the cheeseboard at the party. He draws himself closer, moans a bit. One hand slides down her shoulder, grazes her breast, cups it through the embroidered material of her cheongsam.

She opens one of her eyes, peers out to see where the cab is headed. Down Millbank – good.

He presses closer, and she can feel his erection against her side.

God, this guy tastes like cheese. She realizes how hungry she is, and already knows what his place will be like. There’s probably no food in the fridge, and all he’ll want to do is snort coke and get in her pants.

She doesn’t have sex with people on the same night she meets them. Having to negotiate this is always a hassle.

Somewhere around the Tate Britain, Alex finally releases her from the kiss and catches his breath. His hand is still around her waist.

“So you’ll come back to ours, yeah?”

His lips graze hers again, his tongue reaches in for another kiss.

Halfway across Vauxhall Bridge, she pulls back. No, that’s enough.

“Can you pull over at the end of the bridge?” she asks the driver.

“You’re not coming?” Alex asks, surprised.

“Sorry, I don’t really… do cocaine,” she says.

The taxi slows at the curb, and she opens the door. “I, uh, it was nice meeting you,” she says, one hand on the door handle, the other on his arm.

The late October night blasts into the cab.

“Are you sure?” Alex insists.

“Pretty sure,” she answers. And then she’s shut the door in his startled face, the cold night air drawing goosebumps on her skin, and all she has to do is cross the bridge and be home.

A smile cracks across her face. There is something liberating about just being able to walk out of the cab like that. What had he expected her to do? Go home with him, snort cocaine, have sex with him out of gratitude for the coke? Not so appealing, really.

She thinks of how many other women he’s tried this on, wonders if this deflated his ego just a little bit.

Let it be deflat

ed, she’s happy to sleep in her own bed tonight. And yet, as she crosses the deserted bridge under the waxing moon, a certain sadness undercuts her triumph. As if everything has to end like that – a drunken proposition, a sleazy promise of cocaine, a hand cupping her breast, and an inebriated kiss with a virtual stranger. These kinds of hook-ups are a dime a dozen in London.

She doesn’t really like them, she doesn’t see the point of them, and yet, nothing else seems possible in this city. The road is entirely free of cars, when she crosses it at 3:30 in the morning. The Thames laps its shivering waters alongside the city banks, and her high heels echo against the indifferent pavement.

*

Where they’ve settled in Belfast – him and Michael and Da – is this halting site high up on a hill on the very edge of the city, practically out in the countryside. Actually fuck, it is countryside. Not much to do for your average fifteen-year-old. There’s cows and sheep and all their shite just outside, stinking up the place if the wind isn’t blowing the right way. Fields all around them, but if you look straight ahead facing in one direction, you can see all of Belfast and the sea. All them Republicans and Loyalists and fuck-off murals and the Pakis and the Chinkies and the tourists and whatever else you find in this city.

Belfast is a different enough place from down south, that’s for sure.

But there’s a place where you can hide from it all. It’s just down below. Literally right below his feet if he’s standing at the edge of the field looking at the city. A steep slope right under him, and gurgling away at the bottom, a smallish river and a bunch of trees surrounding it where you can hide. They call it the Glen. He likes the wilder part, where there’s hardly anyone ever around, just the trees and the stream and you feeling all closed in. Private. No one around to fucking bother you.

But if you follow the river down a bit, the valley widens up, there’s less trees and more open grass and people going for walks. And that’s where you can also find some kind of trouble, some distraction, if you’re bored. People passing by to look at, and you can just lie real quiet among the trees, and wait, and wait for someone to come along.

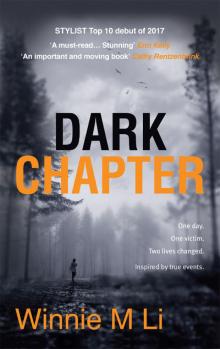

Dark Chapter

Dark Chapter